It’s 8pm – vino-o-clock! – here in Puerto De La Cruz, Tenerife. I’m doing something most un-Spanish: dining solo.

Sitting here on the veranda of a locals’ restaurant, near to my new language academy, Mount Teide – a 3,000m-high volcano – is shimmering in pink, evening light. “The secret of realizing the greatest fruitfulness and the greatest enjoyment of existence is: to live dangerously! Build your cities on the slopes of Vesuvius! Send your ships out into uncharted seas!” so said Nietzsche. I took that instruction to be: buy a language school down-lava from a volcano.

(Below: left – view from the rear of the language school. Right – view from the front.)

Here, in this packed restaurant, half a BBQ chicken – cooked the Canarian way – chips, salad, two large glasses of punchy local red wine, and a coke, plus the obligatory large bottle of local mineral water, has set me back £10. £10! Only a few weeks ago in Manchester I bought someone a pint, which cost £7. (Inflation isn’t crazy over here – think about that).

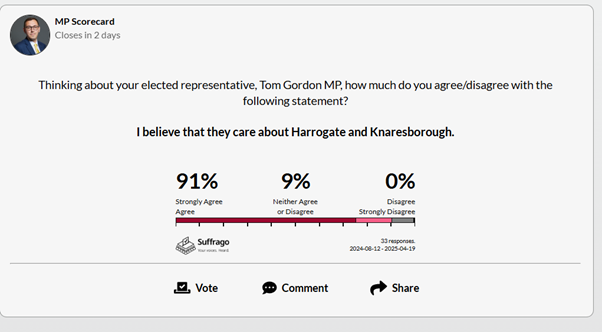

Watching the world go by, I’m reflecting on my first week as the director (the Spanish call it the “administrator”) of my school. Throughout the purchase process, the previous owners have been a class act, ensuring the smooth transition of students and duties.

Fortune shined upon me, as we have hired three talented and experienced teachers, all of whom have the right to work here. And this is no small feat, given the devastation caused by hurricane Brexit, which has reduced the pool of English teachers throughout the EU, causing untold and long-term cultural damage to the UK. Leave or remain, it doesn’t change the fact that UK citizens cannot work as easily as we once did, which is acutely felt in the teaching of English. Irish citizens have no such problems.

This foray into the world education isn’t as crazy as you might first think. Many moons ago, following a graduation ceremony that I didn’t attend, I couldn’t decide whether I wanted to be a teacher or a lawyer, for a degree in Politics, Philosophy and Economics doesn’t really lend itself to anything other than a political special advisor, teaching or law. After an unhappy stint travelling in India, with only a few days’ training, I started work as a Teaching Assistant (TA), in a challenging inner-city high school, in my hometown of Salford.

At this time, Salford City Council had around 500 TAs: I represented half of the male contingent, so female-dominated the TA space was! Pay was around £6,500pa, but the holidays were – naturally – the best that I have known. My role was to guide five Year 7 pupils (the children who have just left the safety of primary school), all of whom have Special Educational Needs (SEN), throughout each lesson, for the year. Essentially, I became part of the class: part bouncer, part teacher, part pupil.

“My” cohort made up a large chunk of what was the bottom set of Year 7. I helped these students in each lesson, often coaxing them to their next lesson, organizing them, keeping them on-point. During each lesson delivered by a bona fide teacher, I had to make notes on each child – their struggles, successes and behaviour. During this time, I witnessed the very best and the very worst of teachers. Many of the teachers treated me with disdain because I was a mere TA: not a proper teacher. But without me, many a lesson would have gone far worse than it did.

“My” children had impossible starts in life. Not only were they “Statemented” in a school which had a poor reputation, in buildings which were ruined by 18 years of underfunding, but some were traumatised refugees who refused to speak due the unimaginable horrors they had seen. For some, their parents were related – i.e. incest was prevalent.

Most of my pupils lived on streets which, to the uninitiated, might appear to be deserted due to the near absence of parked cars. But only when you came to understand these families did you realise that people living on these streets do not own cars, because they cannot afford to do so. This eye-opening experience forever changed my worldview.

Without lessons to prepare and no homework to mark, my working day was 8:50am to 3:15pm, with a lunchbreak. So difficult was the job that, so stressful, that even as super fit 21-year-old, I needed a sleep when I got home. Without equal, it was the hardest job that I have ever had. Much of the behaviour had to be seen to be believed. During one challenging lesson, four teachers were on duty in the classroom, including the Head of Year, plus me, yet we still failed to prevent five children escaping through the open windows. Oftentimes, the teachers were beaten down by challenging lessons, carrying a haunted look. Although people mistakenly think that many lawyers take cocaine, the only time I have seen people use the drug were some teachers on a night out.

One day, I was assigned to a Year 8 boy to help in maths. This lad acted older than his 12 years, wily, larger-than-life, a bully, though quite likeable. I’ll never forget one conversation we had. I have changed his name to David.

…………………………..

“Sir.”

“Yes, David. What is it?”

“We’ve got a new cat.”

“Superb. Now let’s focus on the maths, shall we?”

“Don’t you want to know what it’s called, Sir?”

“If we can get you back to the maths, then you can tell me its name.”

“It’s Strangeways, Sir.”

“Strangeways,” I said, for Strangeways in the notorious prison in Salford, not far from the school. “Why did you name your cat Strangeways?”

“Because my dad got out of Strangeways yesterday and this was the first thing that he nicked.”

…………………………..

What chance did David have? I dread to think what became of him and some of the others. Their predicament was not their fault. I never want to forget that fact. Luck, luck, luck!

I now find myself back in the world of education, unconstrained by bad behavior, Ofsted and pointless bureaucracy. My mother was a teacher, and my father still works in the education world. As I mentioned in my last blog, nature, nurture or both, here we go again, back to my roots, imitating my wonderful parents.

And what of David? Could we really blame him if, like his father, he commits some horrible offence? Or, can he break the vicious cycle through luck, education, positive role models and is own fortitude? On another day, I’ll write on the issue of free will.

I wish David and all those other pupils, and “my” new pupils, all the very best, wherever they are. For me, I’ll do my utmost on the education front. To be an educator, one must be optmistic for humankind. I’m certainly optimistic.