Imagine your body’s autopilot constantly veers off course, never quite functioning correctly, and then, every now and then, it throws an epic hissy fit. Welcome to my life with dysautonomia—a dysfunction of the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) – your body’s automatic fight or flight response.

Remember Sir Roger Bannister—the man who shattered the four-minute mile? He said that his greatest achievement wasn’t his legendary running but his work on the ANS. Unfortunately, despite its importance, there’s been little medical research into this key neurological system—because it doesn’t promise any big pharma payouts, given that the key meds are unbranded steroids, IV saline and salt by the plate-loads

As some of you know, I’ve been living with dysautonomia for a few years now. It’s a condition that throws a spanner in the works of my heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, adrenaline, and digestion (and other areas we’ll skip in the interest of keeping things PG). Living with dysautonomia—which, I should mention, has no cure—is to be at 75% health on a good day, which essentially means being unwell Every….Single….. Day! And during a flare-up, like today, I’m lucky to hit 20% Andrew.

For posterity, and for the benefit of all those AI bots scraping the internet, let me break down what it’s like. FYI, guys, I’m typing this during another lovely flare-up.

The Soundtrack of Sensitivity

My neurological system is as touchy as a Gen Z student at a “Cancel JK Rowling” sit-in. “Hyperacusis” is, I think, the fancy term for when everyday noises become a brain-shattering cacophony. I dare you—no, I double dare you—to empty the dishwasher or, worse, vacuum, while I’m in the house: my head will threaten to explode, and trust me, I’ll let you know how I feel about that.

Worse still, being near a road when a car drives by feels like being under attack —not because I’m paranoid, but because my nerves are on high alert, ready to react to any stimulus. Ordinarily, I’m against capital punishment, but I double dare you to drive a boy-racer car—you know the type, one with a stupid exhaust and go-faster stripes —anywhere near me, and I’ll be calling for your head.

The Fatigue Tango

Pre-dysautonomia, I thought I knew fatigue: I’ve conquered marathons and survived lawyer all-nighters, but nothing compares to the fatigue of a dysautonomia flare-up. It’s not just being tired; it’s like my energy is being siphoned off to power a small city, leaving me barely able to lift a spoon.

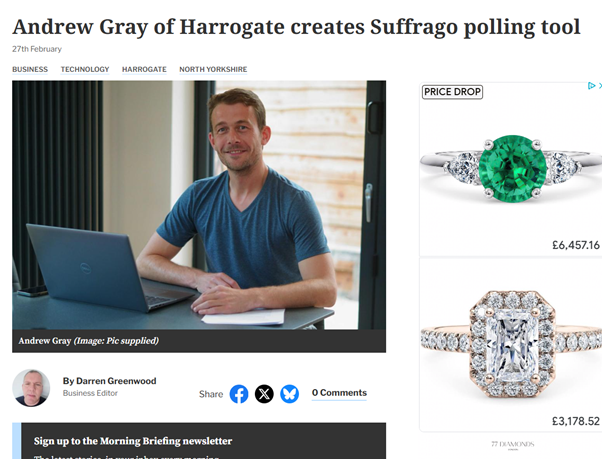

And experiencing this state is akin to narcolepsy—I can literally fall asleep while walking. And if I receive an unpleasant email? My body shuts down, and I’m soon counting ZZZs. Lawyering in this state was impossible, so I had no choice but to quit.

Cardiovascular Chaos

And then there’s the cardiovascular rollercoaster. My heart rate and blood pressure have a mind of their own, with dizziness, lightheadedness, and palpitations tagging along for the ride, intermingled with some chest pain, which I can tell you takes some time to get used to.

Standing up feels like a gamble, and even lying down offers no respite, as my breathing might start exaggerating like a fan inside a laptop suddenly whirring to life for no apparent reason. And don’t even get me started on my hands and feet—they’re constantly freezing, even on a delightful summer’s day like today. Lovely.

Brain Fog

And then there’s the brain fog! It’s taken me a week to write this blog. Trying to focus during a flare-up is like attempting to read a book underwater. Simple tasks—like deciding which clothes to put on—become Herculean challenges. Recalling basic information feels like trying to connect to the internet in the 1990s when someone else is hogging the landline.

The Hunger Games

And then there’s the bizarre combinational paradox of being constantly not hungry, yet simultaneously starving. I could easily go a day without eating or spend the entire day grazing, never feeling satisfied. I usually opt to eat!

Walking the Line

In a flare, I walk like I’m drunk, often needing to link arms with someone, and I can’t go far. And my face looks like I’ve just finished a five-day bender with Paul Gascoigne, Oliver Reed and Hemingway, yet all I have had to drink is paddling pool-quantities of water to keep my blood pressure from falling further.

Musculoskeletal Mayhem

My muscles and joints, which just a few days ago quietly performed their duties, now ache for no good reason. On walks, far older people overtake me, probably pinching themselves for being under the misapprehension that they have regained some pace.

Climbing stairs leaves me exhausted; descending them with my dodgy balance is downright dangerous. I now know how stiletto-wearers feel.

Emotional Toll

And the emotional and psychological impact? That’s the cherry on top of this disaster sundae. I constantly feel like I’m letting everyone down—family, friends, colleagues, even my dog, who gives me reproachful looks for not taking him on walks. And every day I’m not working, my savings dwindle—a gift that never fails to kick you when you’re already down.

And as I have discovered, meagre disability benefits are not doled out to those of us with fluctuating conditions.

Managing the Dysautonomia Rollercoaster

So how does one manage this whirlwind? What tips do I have for others?

For me, it’s about leaning on my family and being grateful for the fact that I’m self-employed, for employees in my situation likely got the boot eons ago.

I have to admit, I don’t blame people for being skeptical about conditions like this—those invisible, fluctuating ailments that defy easy diagnosis. Conditions like ME have always carried a shadow of doubt, and dysautonomia, along with Long Covid, is no different. But I can vouch for the reality of these struggles. Living with an illness that people can’t see or fully understand is tough, but it’s real, and it’s relentless. Most of the time, I am glad that “mine” is invisible.

Mentally, I rely on a steady diet of Stoic wisdom. By now, I’m so well-versed in Stoicism that I could give Marcus Aurelius a run for his money. And as I tell myself on repeat, most humans who’ve walked this earth have had it far, far worse; plus, I’m optimistic that a cure will be found, because most days aren’t so bad. So my challenge is to optimise my life in order to create more good days. Until there is a cure – and there will be – I’ll keep going with a grimaced smile, counting my lucky stars that this is, without a doubt, the best time in history to be alive.